Francdemic - How Polish Swiss franc borrowers have been affected by the covid-19 pandemic

Author: Mathias Krabbe

In a finding that will likely surprise nobody, "koronawirus" is the word of 2020 in Poland according to a poll by the Institute of Polish Language at the University of Warsaw and the Polish Language Foundation. It is a word that most people are overly familiar with and that needs no translation, introduction, or explanation - even if one would doubt the existence of the virus, nation-state responses to it have been series of restrictive measures such as social distancing, mandatory masks, as well as "lockdowns" (another hot buzzword) of private and public institutions, workplaces and businesses that have been surely felt by everyone.

Right from the get-go, these national responses to the pandemic were considered a threat to the well-being of the national economy and the interests of those who invested in its growth through various financial instruments. However, some Polish households have been exposed to financial stress that was also related to the pandemic but mediated by their connections to global financial markets rather than the national economy. This was the case of Polish mortgage borrowers with loans indexed or denominated in a foreign currency, in particular the Swiss franc (CHF). Similar kinds of mortgage loans were introduced in other Eastern European countries such as Croatia and Hungary during the early 2000s and have been marketed as low-risk and safe. These loans exposed borrowers, often without their full awareness of the fact, to interest rate and exchange rate risk. The consequences for their financial well-being became especially clear in the wake of the Global Financial Crisis of 2007–2008 as massive franc appreciation against Eastern European currencies led to rampant overindebtedness and defaults among borrowers. Most governments in the region responded by converting outstanding Swiss franc loans to national currencies. Poland was an exception from this pattern and today there are still almost 800,000 people living with their CHF mortgage loans.

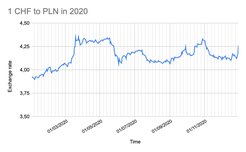

Whereas national economies around the world saw a general slowdown due to mandatory lockdowns, stock exchanges such as NASDAQ kept going up, to the disbelief of many, effectively, increasing the wealth of investors - the two most prominent examples being Jeff Bezos and Elon Musk. Yet for Swiss franc mortgage borrowers the fluctuations on the financial market had a different outcome. They saw the appreciation of the Swiss franc against the Polish zloty once again, which has happened several times over the previous decade (see the graph below for the year 2020).

For comparison, on 4 February 2008 the CHF/PLN exchange rate was 2.2. The most memorable episode of the long ensuing period of franc appreciation was the so-called "Frankogeddon" (a word-play on Armageddon and Swiss franc) in January 2015 when the Swiss National Bank unpegged the franc from the euro in a surprising move, causing the currency to float and become more sensitive to market fluctuations. The immediate consequence was another significant appreciation of the franc, which for the Polish CHF borrowers effectively translated into an increase in their outstanding debts. At the same time, the value of the real estate purchased with these mortgage loans has in most cases not grown sufficiently fast to offset the capital losses of debtors.

Not all is doom and gloom. In 2019, the Court of Justice of the European Union (CJEU) ruled in favor of the Dziubak family in their proceeding against Raiffeisen Bank International AG, which for many borrowers has rekindled the hope that contesting their franc loans in courtrooms might be successful. This does not necessarily mean that the fight is over, and it is not the first time that CHF borrowers have felt close to victory. In the past, they have been encouraged to do so by campaign promises of Andrzej Duda, the then presidential candidate of the ruling Law and Justice Party (PiS) and now president. These promises have yet to materialize into legislation that would once and for all rid borrowers of their connection to the foreign currency. The hope that such legislation would materialize was extinguished in 2017 by the leader of PiS Jarosław Kaczyński who has urged borrowers to turn to the courts in individual lawsuits. After the recent CJEU verdict coupled with the additional financial stress due to the pandemic, many debtors are doing just that. In fact, in 2020 alone almost 20,000 new lawsuits have been filed by individual households, a fourfold increase compared to 2019. The sheer number of filings and the on-going pandemic are presumably affecting the speed with which courts will be capable of delivering verdicts. Thus, for the foreseeable future, financial uncertainty continues to loom large for Polish franc borrowers.