The Food Sharing Debate: A Case Study from Siberia

The Food Sharing Debate: A Case Study from Siberia

First, we give meat and fish to the old people, then we give to others who need it, and finally, we leave some for ourselves. This is our law. Vitaly Porotov, Dudinka, 2001.

Note, keeping meat for oneself (dlia sebia), a concept that include one's family and kin, is last on the distribution list behind elders and other people. In addition to Porotov's formulation, I have documented a number of traditional rules and viewpoints that justify and encourage food sharing with people beyond the family. For example:

If I get a caribou, I am obliged to give away some of the meat. I mean if I did not give some away, the hunt does not happen. It is that kind of nature. We share, if we catch game. Sergei Turdagin, Ust Avam 1997.

Traditional cosmological understandings may be a significant motivational force for food sharing in the community. While they are passed on from ancestors to descendants, these rules and obligations encourage cooperation among a wide set of individuals, and maintain egalitarianism in the community.

Kinship and Friendship in Native Siberian Communities

The social context in my study community is one where there is a relatively high density of genealogical and affinal relationships. For example, my earlier research found that the average number of genealogical relatives in the community was 35. That is to say that approximately 5 percent of the population is genealogically related to the average person. Affinal relatives increase the circles of kinship in the community to the point where many informants say, "Half the village are my relations."

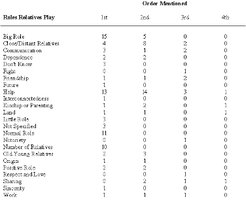

Table 1 shows the answers to the question "What role do relatives play in your life?" The most popular roles for kin were: "help" (pomoshch) and "a big role" (bol'shaia rol'). Answers to this question can be divided into two sets: 1) socially expected behavior patterns of kin and 2) concepts about kinship, such as old/young, and close distant. This wide set of answers may be due to the openness of the question. Note that kinship and friendship concepts are not mutually exclusive according to the survey results. A number of Dolgan and Nganasan informants stated that the role of relatives was friendship.

Although I did not ask a similar question about friends, there is anecdotal evidence that the expectations for friends are likely to be more reciprocal than those for relatives. One good friend of mine suggested to me that a number of his supposed local friends had recently borrowed tools and not returned them, but rather, lent them to someone else. He recalled during the Soviet period he was not quite so concerned about such behavior, because tools were available in the store. Now in the post-Soviet period, when access to resources has diminished, failure to reciprocate is likely to more easily end a friendship. This points to the greater conditionality of friendship over kinship.

Study 1: Sharing of Unprocessed Country Food

I will now discuss the design and the results of three studies that I have done on food sharing in the Siberian arctic. The first study was part of structured interviews of 79 household heads in the Ust Avam community in 1997. These households represented approximately one half of those in the study community. Two questions were related to food sharing. One question was "To whom do you give meat and fish?" This was an open-ended question and the answers are shown in rank order in Table 2. The answers to the first question indicate that relatives are the most common recipients of meat and fish, followed by friends and other people, such as pensioners, single mothers and other people who ask. Neighbors are less common recipients.

Informants were also asked the question, "From where, or from whom, do you get meat and fish?" About half of the informants replied that they got meat and fish only from the tundra (i.e., through their own efforts). This points to the local importance of subsistence hunting, fishing, and trapping for family livelihood. The other half replied that they got meat and fish gifts from relatives and friends, either alone, or in combination with their own foraging and purchasing. Twenty five percent of the respondents mentioned purchasing as the main source (5%) or supplemental source (20%). Similarly, the second question showed that beyond their own subsistence efforts, relatives, friends, and purchases were strategies used to obtain the most important components of the diet. It should be noted that virtually all meat and fish was purchased prior to 1991. Hunters were obliged to turn in the products to state enterprises and keeping products for ones own use, barter, or sale was punishable.

While these questions do not test the relative importance of one modes of distribution over another for a given type of social relationship, the results do indicate the level of local emic importance of kinship in food sharing and transfers. People who cannot support themselves are taken care of, and exactly at the levels as expected from the "law of sharing" as Vitaly formulated above, where they would be the second most popular receivers of food. The results of Study 1 show that kin are receiving more food than unrelated village elders in general, however, where according to Vitaly's law of sharing, they should be given food first. How food is actually distributed helps to resolve this contradiction. Young hunters often bring meat and fish catches directly to their parents, elder sisters, or wives. Many kin recipients of food are in fact elders.