The Food Sharing Debate: A Case Study from Siberia

The Food Sharing Debate: A Case Study from Siberia

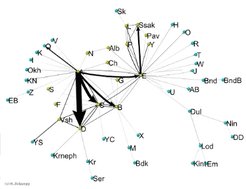

A social network approach to resource flow and reciprocity reveals more information than a multidimensional scale. The position of households determined by their similarity to each other with regard the households with whom they share meals as above. The size of the arrow indicates the relative number of observations of Household B eating at Household A.

The network in Figure 2 is sparse. Only about 10 percent of possible ties are present. Of the two most observed households, they have 15 and 16 sharing households respectively. The network shows a well-connected core, where most of the households can reach other people in three steps on average. The periphery, represented by blue points, is where households are connected to most others by four to six steps.

Another characteristic of the network is inequality. Many actors are more active as hosts than others. This may be an artifact of the way the data were collected-focal following of members of households A, B, C, D, and E. Nevertheless, the graph represents a fairly complete picture of the interhousehold meal events of those households over a year.

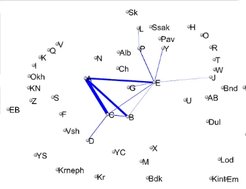

The next figure identifies the cases where there are reciprocal ties, and indicates their relative strength by the thickness of the line. The network is characterized by little reciprocity (Figure 3). Reciprocity is present between households where relationship is characterized by high levels of kin relatedness and also between households where there is little or no kin relatedness. In these cases the relationship would be characterized by friendship.

In summary, households with close kinship links have the most assymetrical hosting of meals by elder generation. This might be expected based on kinship theory, where the lion's share of resources flow from ancestors to descendants, especially those in infancy, youth, and young adulthood. Reciprocity meal hosting occurs, but reciprocity is not necessary for meals between relatively close kin in different household-an example is household A (the elderly parents) and D (the young couple with newborn child). Reciprocal meal hosting appears to be important for members of different households, unrelated by kinship. Thus, six of the seven households with whom household E reciprocally shared meals are friends of household E and only one is related through close kinship. Representatives of many households who are linked neither through kinship or reciprocity are also hosted at meals. These are the peripheral households portrayed with blue dots. Thus, evidence for social leveling through food sharing at meals is provided. These patterns still need to be checked with patterns of actual kinship relatedness and patterns of economic need, for which similar graphs can be generated, in order to check the importance of each of these variables in food sharing networks.