The Food Sharing Debate: A Case Study from Siberia

The Food Sharing Debate: A Case Study from Siberia

Study 2: Sharing of Meals

In the second study a rigorous test of food sharing models in the Dolgan and Nganasan subsistence economy is possible. The study focused on food sharing at meals, using records of meals I collected during my dissertation research. Meals are potentially important to the food-sharing debate for a number of reasons. First, foods consumed at meals include the value added to the product during preparation. The additional value originates from the time and labor invested in processing and cooking, as well as any supplemental foods that enhance taste. Thus, giving away a valued-added product increases the costs of transfer over unprepared foods. From a cost-benefit standpoint, one would expect the benefits received to be greater than those received upon transfer of equal amounts of unprepared food. Second, in the Dolgan and Nganasan study communities discussed here, the practice of visiting relatives and friends is an important part of daily life, being one of the main social activities. Hosts are invariably hospitable, and food is almost always served to guests. If this reciprocal sharing at meals is occurring often enough, inter-household food sharing at meals may be a significant venue for risk-buffering exchange. Third, in the daily life of hunter-gatherers, production, distribution, and consumption are interrelated components of the socio-behavioral continuum. Depending on division of labor in society, inter-household sharing at meals may turn out to be more important than previously thought, especially if sharing at meals is a form of return payment for earlier transfers of unprepared food, other kinds of assistance, or a venue for information sharing about who has what food.

In this analysis I grouped meals into three types of locations (bush, village, city) and compared the relative proportion of different kinds of social relationships characterizing the participants in the meals. I selected 814 meals from the 1995/1996 field season. Within this data were 546 shared meals, 303 of which were interhousehold meals. The other 268 meals were shared only between members within one household. In the interhousehold meals members of 50 households observed as hosts or guests. Most observations were made in 3 households, multiple observations in 15 households, single observations in 9 more households. Households were defined by coresidence in a village apartment or hunting cabin based on my reading of the village registry book and my community census. In a number of cases husbands are listed in the registry book as the sole member of a separate household so the family can receive single-mother payments. Thus, coresidence was used to define a household. This definition could be problematic in some respects, since Soviet housing policy focused on nuclear families and small apartments. One might find extended families, which have people living in a number of apartments in the village, plus regularly living in a hunting area, but where people coordinate their activities to some extent. However, by using a consistent definition of the household, which has been imposed by the living conditions of the village, one can make an initial appraisal of food sharing behavior. Alternative definitions of "household" would likely result in different outcomes.

At meals in the bush (hunting trips, etc.) participants are most commonly close agnatic kin. Relatively high proportions of spouses, affines, and friends of both sexes characterized village meals, while higher proportions of females and their cognatic relatives and friends characterize city meals. These differences indicate a flexible social organization that has adapted to the social and political context of the Soviet North. The village has become in effect a permanent meeting spot, where cooperation between individuals from different households is likely reflected in shared meal. The bush reflects the importance of kinship cooperation in hunting. The city reflects the trend for female migration to the city and reliance of people living in villages upon relatives in the city for a base while on visits.

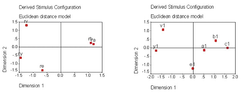

Developing a technique to compare kinship and reciprocal meal hosting was the next step. Multidimensional scaling represents the differences between each actor, in this case households a, b, c, e, y, and v, the six with the highest number of interhousehold partners in the dataset. On the left graph in Figure 1, I used the average household relatedness of each cooperating household based on the individual genealogical relatedness of each pair of individuals in each household. Non-related people in the household, such as spouses without children, lower average household relatedness and create more distance in the graph. In the graph on the right, the same six households are compared in terms of the numbers of meals hosted versus the number of meals in which they were guests for each of the five other households. The distance between the points indicates the degree of dissimilarity between each household in term of interhousehold meal sharing. Kinship (left) and reciprocal meal hosting (right) appear to be structured similarly. Does this lead me to the proposition that Gurven et al. (2002) make (i.e., much of what was assumed to be kin-selected behavior in humans may actually be reciprocal altruism)? One might as easily argue the other way, much of what we thought of as reciprocal altruism may be kinship.